Why is so much writing, especially academic prose, so hard to read? We’ve all encountered it: dense paragraphs filled with jargon, convoluted sentences that require three readings, and explanations that somehow manage to be both technically correct and utterly incomprehensible. The problem is so pervasive that it feels almost inevitable. Surely, we think, complex subjects demand complex writing.

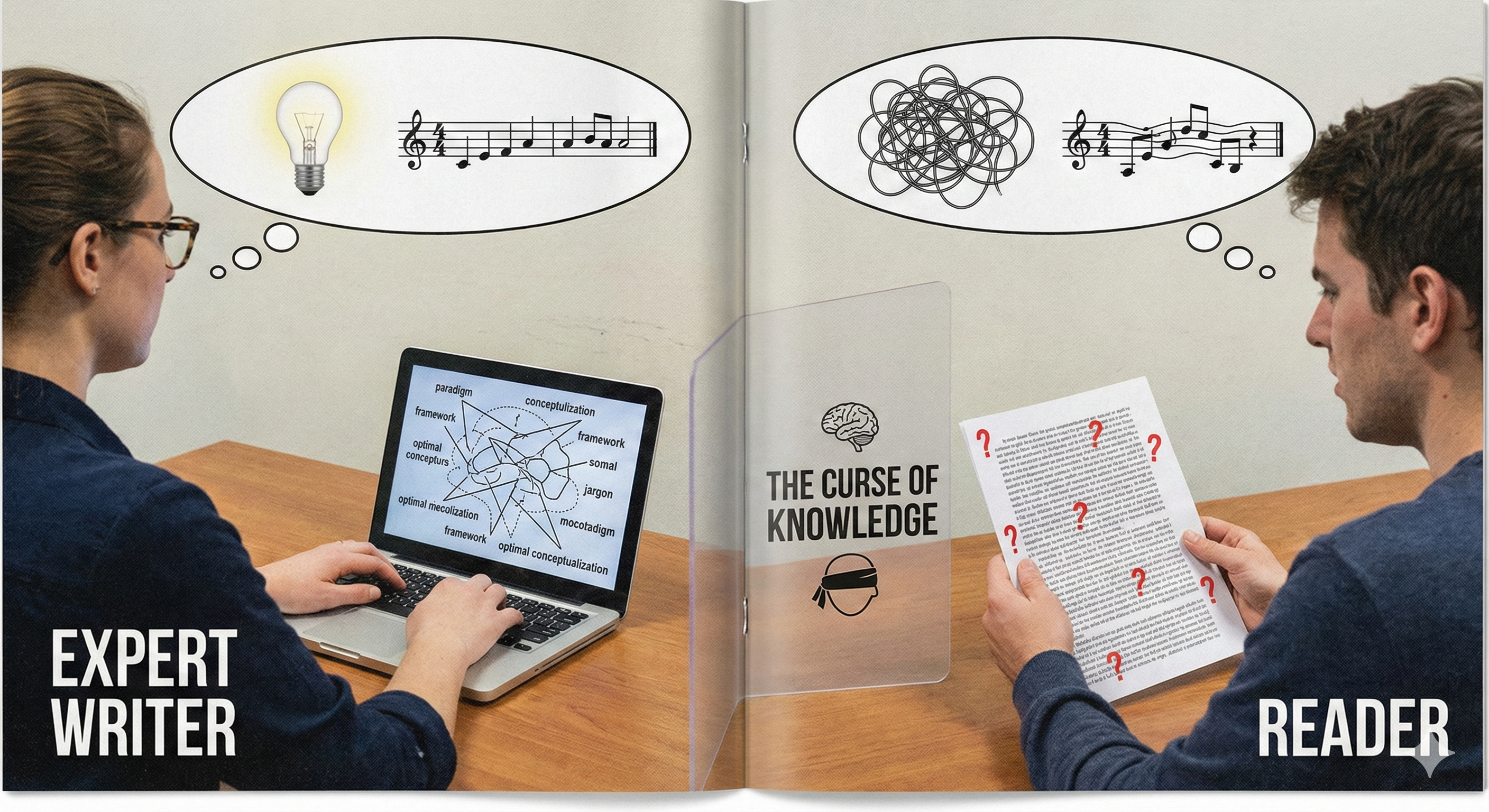

But cognitive scientist Steven Pinker offers a different, more hopeful answer in The Sense of Style: the curse of knowledge. This mental blind spot makes it extraordinarily difficult to imagine not knowing something once you know it. Pinker calls it “the failure to understand that other people don’t know what we know” and deems it the chief culprit behind unclear, turgid writing. In other words, experts omit crucial details, assume jargon is obvious, and skip logical steps, unaware that their readers aren’t in on the same information. The result is prose that’s technically correct yet opaque to its audience.

Understanding the Cognitive Trap

The curse of knowledge is a predictable cognitive error that affects even the most well-intentioned writers. Psychologists have shown that even when we try to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, we struggle to shed our own knowledge. Adults may outgrow the most blatant childhood egocentrism, but we still systematically overestimate what others know and understand.

Consider a classic experiment that perfectly illustrates this phenomenon. A “tapper” morse-coded a familiar tune on a table and predicted listeners would recognise it about 50% of the time. The tapper could clearly hear the melody in their head, “Happy Birthday,” perhaps, or “The Star-Spangled Banner.” But listeners, hearing only a series of knocks, guessed the tune almost zero percent of the time. They couldn’t hear the melody that played so vividly in the tapper’s mind (Camerer et al., 1989).

Seasoned writers fall into the exact same trap with readers. Studies find that subject-matter experts wildly over-predict how well novices will grasp technical content, thanks to knowledge that “seems too obvious to mention” to the expert but isn’t obvious at all to the novice. In one influential study, researchers found that expertise doesn’t just add knowledge, it fundamentally changes how we predict others’ understanding, making us terrible judges of what needs explanation (Hinds, 1999).

Think about how a psychologist might describe an experiment: “stimulus intensity modulating response duration.” What actually happened? Children stared longer at a bunny than at a truck. The abstraction completely hides the mental image that made the finding meaningful in the first place. The psychologist isn’t trying to confuse anyone, they’ve simply lost touch with what it feels like not to know the technical terminology.

Beyond this cognitive bias, academics often write under what Pinker calls “agonising self-consciousness,” teetering between over-explaining and trying to sound scholarly. In his 2014 Chronicle of Higher Education essay, Pinker dismisses some convenient excuses for bad writing. “Deliberate obfuscation” and “academic subjects are just inherently abstract and complex”, these factors exist, he says, but they’re overrated as causes. Many scholars with nothing to hide still churn out convoluted paragraphs. Much of bad writing comes from writers being overly cautious, abstract, and insider-focused, forgetting to simply communicate with the reader.

The uncomfortable truth? You cannot reliably detect the curse of knowledge in yourself. Empathy alone doesn’t work because the problem is that you no longer know what needs explaining. Your expertise has reorganised your mental landscape so thoroughly that you’ve forgotten which stepping stones you used to climb to your current understanding.

Strategy 1: Recruit Outside Readers

If the diagnosis is cognitive bias, what’s the cure? Pinker’s most reliable solution is external feedback from intelligent people outside your field. This isn’t about dumbing down your writing or avoiding technical content, it’s about calibrating your assumptions to reality.

Pinker himself famously gave drafts of his books to his mother, not because she was unintelligent, but precisely because she wasn’t a cognitive scientist. She could tell him exactly where his expertise had blinded him to gaps in explanation. A colleague from another field or an actual novice can serve the same purpose. As Pinker notes, “You’d often be surprised to find that what’s obvious to you is not obvious to anyone else.”

This feedback doesn’t need to be comprehensive literary criticism. Sometimes the most valuable input is simply: “I got lost here” or “Wait, what does that term mean?” These moments of confusion are gifts, they pinpoint exactly where you’ve made unwarranted assumptions about shared knowledge.

The practice of seeking outside readers should extend beyond a single draft. Pinker urges writers to revise explicitly for clarity, even in later stages where you aren’t adding new content. This means systematically iterating purely to make the prose simpler and more understandable. It’s not about new ideas, it’s about making existing ideas accessible. If your writing has never confused a reader outside your immediate peer group, it probably hasn’t reached anyone outside it.

Strategy 2: Descend the Ladder of Abstraction

Pinker describes effective prose as a window onto the world. The goal is not to shuffle words around but to allow the reader to reconstruct a scene, an action, or a causal chain in their own mind. When this works, reading feels effortless, ideas simply appear in your consciousness. When it fails, reading becomes an archaeological dig through layers of abstraction.

Abstract language makes mental reconstruction nearly impossible. Words like “paradigm,” “framework,” “context,” and “process” don’t point to anything you can see or imagine. They float above experience, gesturing vaguely at concepts without grounding them in the physical world. Concrete language, by contrast, anchors meaning in perception, motion, and physical objects, things we evolved to understand intuitively.

This is where what writing experts call “the ladder of abstraction” becomes crucial. Generalisations are useful because they compress information and reveal patterns. Examples are useful because they make ideas intelligible and memorable. Either one alone is inadequate. Generalisations without examples are vague and forgettable. Examples without generalisations seem trivial and pointless. Effective writing moves smoothly between the two levels.

State a principle, then immediately ground it in a concrete example. Describe a specific action, then explain why it matters more broadly. If you write “the patient exhibited pathological aggression,” you’re forcing the reader to guess what that looks like. They might imagine anything from mild irritability to violent assault. If instead you write “the patient grabbed the nurse by the throat,” the meaning is instant and vivid. The reader can see it, and now you can build analysis on that shared mental image.

Pinker emphasises what he calls “classic style”, writing where the author points to things in the world that the reader can see. Instead of piling up abstractions and jargon, classic style uses clear examples and visual metaphors to ground complex ideas. Rather than writing “The level of stimulation was reduced,” one might say “We turned down the volume.” The latter paints a picture and is immediately graspable.

This approach isn’t “dumbing down” complex concepts, it’s revealing the concept’s essence in relatable terms. In fact, excessive abstraction often indicates the writer themselves hasn’t fully connected with their own idea. By forcing yourself to give a tangible example or scenario, you clarify your own thought and make your writing far more engaging.

Pinker notes that 18th- and 19th-century prose often feels more vivid and direct not because those authors were more talented, but because they lacked layers of modern academic abstraction. They had no choice but to describe what happened in the world without today’s shorthand.

Whenever you catch yourself writing about ideas rather than things, stop and ask: What would a camera see? What would I hear, touch, or smell? This simple test instantly reveals whether you’re showing readers something real or just waving abstract concepts at them.

Strategy 3: Listen to Your Prose

Clarity is necessary, but it’s not sufficient for good writing. Writing is also an auditory experience. Readers silently “hear” sentences as they process them, complete with rhythm and stress patterns. This isn’t a metaphor, it’s how the brain processes language.

Pinker argues that awkward prose disrupts comprehension because it disrupts rhythm. When sentences are too long, too tangled, or badly balanced, the reader has to work to keep their place in the sentence. That cognitive effort distracts from meaning. You’re asking readers to simultaneously parse grammatical structure and extract ideas, a recipe for mental overload.

The simplest diagnostic tool is reading your work aloud. When you read your own writing out loud, convoluted sentences and jarring jumps in logic become immediately apparent. If you stumble, mumble, or get lost while reading, your text likely needs smoothing. This technique externalises the writing and engages multiple senses, helping you catch overly long, awkward constructions that silent reading might gloss over. Many editors and writing coaches advocate the “read it aloud” test as a fundamental way to ensure your sentences flow and make sense on a basic human level.

Attention to sound doesn’t mean ornamentation or purple prose. It means avoiding unintentional ugliness. Clusters of hissing consonants (“the assistants insisted the system’s insistence”), repeated filler phrases, and endless subordinate clauses create friction. Occasionally, light alliteration or parallel structure can add pleasure to prose, but only when it’s subtle and serves meaning rather than drawing attention to itself.

Brevity matters for the same reason rhythm does. Cutting unnecessary words forces decisions about what really matters. It pushes writers toward concrete verbs and specific nouns instead of vague, meandering phrases. Shorter sentences aren’t always better, variety in sentence length creates a pleasing rhythm, but unnecessary length is never helpful. Every word should earn its place.

Good prose doesn’t draw attention to itself. It disappears, leaving only the idea behind. Like a clean window, the writing should be invisible, all your reader sees is the world you’re showing them.

Strategy 4: Slay the Zombie Nouns

Watch out for what writing expert Helen Sword calls “zombie nouns”, abstract nominalisations (often ending in -tion, -ment, -ance, or -ism) that sap the life from your sentences. These walking dead infest academic writing, turning vibrant actions into static things.

For example: “There was confirmation of the need for implementation of the plan” is grammatically correct but painfully abstract. Revived into a living sentence, it might read: “The results confirmed that we need to implement the plan.” By turning nouns back into strong verbs, you make the statement shorter, clearer, and more dynamic.

Academic writers often pile up noun phrases, what Sword terms “noun plague”, in an attempt to sound objective or serious. But they end up with an impenetrable wall of words that exhausts readers. Bold, active verbs and concrete subjects create momentum and imagery, whereas strings of nouns and vague terms create what editors call “fog.”

Be especially wary of turning vibrant actions into nouns. “Analysis of the data was performed” becomes “We analysed the data.” “The hypothesis was subjected to testing” becomes “We tested the hypothesis.” Notice how the active-verb versions are not only shorter but also clearer about who did what. They restore human agency to the sentence.

Prefer “explained the hypothesis” over “provided an explanation of the hypothesis.” Choose “decided to proceed” instead of “made the decision to proceed with.” Your sentences will be more direct, more energetic, and far easier to parse. The reader’s brain can process actions much more efficiently than abstract states of being.

This isn’t just stylistic preference, it’s cognitive science. Our brains evolved to understand agents performing actions on objects. When you write in this natural pattern (subject-verb-object), you align your prose with how readers’ minds work. When you bury actions in nominalisations and abstractions, you force readers to do extra mental work to reconstruct who did what.

Strategy 5: Build Clear Pathways

Even a brilliantly organised argument can lose readers if the writer doesn’t cue the connections between ideas. Weak or missing transitions force readers to play detective, piecing together how one point relates to the next. This extra cognitive work worsens comprehension and makes readers more likely to give up.

Pinker complained about the “clunky transitions” and sudden jumps that plague academic writing. To avoid this, use explicit transitional phrases and ensure logical flow. Words like “However,” “For example,” “As a result,” “Meanwhile,” and “In contrast” act as gentle guides, preventing reader whiplash. They’re signposts that tell readers where they’re going and how the upcoming idea relates to what came before.

Each sentence should follow logically from the previous one. If you find two adjacent sentences don’t connect smoothly, you have two options: add a bridge or rearrange the order. Think of cohesion as a courtesy, you’re letting the reader effortlessly follow your train of thought instead of making them work to reconstruct it.

Additionally, make sure pronouns and references are unambiguous. A common curse-of-knowledge slip is using “this” or “it” without a clear referent, because you know what “it” refers to, but your reader might not. “This approach failed” is ambiguous if the previous paragraph discussed three different approaches. “This experimental design failed” is clear.

Good transitions are like signposts on a road. Without them, even a well-built road can leave travelers lost and frustrated. With clear markers, readers can focus on the scenery, your ideas, rather than worrying about whether they’re going the right way.

The Research Supporting Simplicity

These aren’t just style preferences, they’re backed by empirical research on how readers process and judge writing. In a fascinating study, psychologist Daniel Oppenheimer asked participants to rate the intelligence and credibility of writers based on their word choices. Readers consistently judged writers who used plainer language as more intelligent and credible than those who used needlessly complex vocabulary (Oppenheimer, 2006).

In other words, stuffing your essay with obscure vocabulary can backfire spectacularly, creating an impression of insecurity or pretentiousness rather than expertise. As Oppenheimer put it in his wonderfully ironic title: “Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly.” Or more simply: avoid big words when simpler ones will do, because readers see through it and prefer clarity.

The takeaway is profound: clarity isn’t condescension; it’s a mark of respect for the reader’s time and cognitive load. Good writers choose the concrete over the abstract not to oversimplify, but to invite understanding. They understand that the goal isn’t to impress with vocabulary, it’s to transfer ideas efficiently from one mind to another.

Writing in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

The rise of large language models complicates the picture in interesting ways. Modern AI systems like ChatGPT can produce grammatically sound, well-structured text at impressive scale. Pinker has weighed in on this development, noting that LLM outputs are often “well written in the sense that they aren’t in academese or jargon. The sentence structure tends to be pretty plain and sound. Even the progression of ideas tends to be orderly” (Pinker, 2025).

This technical prowess might suggest that the “science of good writing” can simply be automated, that we can outsource clarity to machines. However, Pinker and other experts emphasise a critical caveat: style is not substance.

While AI prose may be free of grammar errors and structural problems, it lacks insight, creativity, and judgment. Pinker observes that LLM-generated text is “so generic and prosaic” that you can often recognise it as machine-made due to its bland uniformity. The model stitches together likely combinations of words from its training data, essentially a “mashup” or “pastiche” of what humans have already written. It has no true understanding of the facts or ideas it’s putting into sentences.

As a result, AI-written passages, though grammatically correct, tend to be formulaic and shallow. They seldom offer fresh metaphors, striking insights, or a discerning take on an issue, those require a depth of cognition and real-world experience that AI simply doesn’t possess.

Pinker points out that an LLM has “no lived experience or goals”; it cannot decide what is important or how to angle a narrative beyond statistical imitation. This leads to what might be called insipid competence: the text is smooth but often says nothing new or incisive. The sentences scan correctly, but there’s no there there.

In practical applications, AI can assist with boilerplate writing, the rote parts of legal documents, form letters, or basic summaries. Automating those mundane drafts could save human effort for creative and analytical heavy lifting. But when it comes to writing that requires original thought, wit, or careful judgment, AI falls flat. It might produce a superficially fine paragraph, yet miss the core message or misjudge what the audience cares about.

Clarity with insight remains a uniquely human strength. AI cannot choose to emphasise one idea over another, inject a purposeful style, or exercise discretion about what not to say. It has no “curse of knowledge” only because it has no knowledge at all, merely a statistical veneer of it.

Looking ahead, Pinker and others see AI as a tool, not a replacement for writers. An AI assistant might help spot convoluted sentences or suggest alternative phrasings, functioning as a super-charged grammar checker. It can generate a first pass at routine documents or summarise background information. But genuinely good writing, the kind that engages, persuades, or enlightens, requires discernment about what your reader needs, which points are meaningful, and what tone is appropriate. Those are decisions of judgment and creativity that no algorithm currently matches.

Ironically, the ubiquity of AI may raise the bar for human writers. When generic text becomes cheap and abundant, insightful, original voices become even more valuable. As AI-generated prose saturates the internet, writers who can deliver a clever turn of phrase, an unexpected analogy, or a deep analysis will stand out. Fresh metaphors and creative expressions will be “more valuable,” as Pinker suggests, in an era when bland baseline text is plentiful (Pinker, 2025).

Putting It All Together

The science of good writing teaches us that clarity comes from empathy and concrete thinking, habits we must consciously develop to overcome our cognitive biases. The curse of knowledge isn’t something we can eliminate through sheer willpower, but we can develop practices and systems to work around it.

Write with the reader in mind, always. Recruit outside readers to catch your blind spots. Climb down the ladder of abstraction to ground your ideas in concrete reality. Read your work aloud to catch awkward rhythms and unclear passages. Eliminate zombie nouns and restore vigorous verbs. Build clear pathways with explicit transitions and unambiguous references.

Say it simply, but not at the expense of substance. Use tools like reading aloud, outside feedback, and even AI-based suggestions to polish your grammar and structure. But remember that insight and style cannot be automated. No algorithm can tell you what matters, what’s surprising, or what your specific reader needs to know.

Good writing remains both an art and a science: a craft honed by understanding how readers think, and an art elevated by the creativity and humanity a writer brings to the page. As Pinker reminds us, writing is not self-expression, it’s successful mind reading. Your job as a writer is to reconstruct your thoughts inside someone else’s head, bridging the gap between two minds with nothing but marks on a page.

That’s the challenge. And thankfully, cognitive science can help.

References

- Pinker, S. (2014). The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. New York, NY: Viking.

- Pinker, S. (2014, September 26). Why Academics Stink at Writing. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G., & Weber, M. (1989). The curse of knowledge in economic settings: An experimental analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 97(5), 1232–1254.

- Hinds, P. J. (1999). The curse of expertise: The effects of expertise and debiasing methods on prediction of novice performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 5(2), 205–221.

- Oppenheimer, D. M. (2006). Consequences of erudite vernacular utilized irrespective of necessity: Problems with using long words needlessly. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(2), 139–156.

- Sword, H. (2012). Stylish Academic Writing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pinker, S. (2025, June 4). Steven Pinker: Rules for Writing and AI’s Impact. Interview by D. Perell. How I Write (podcast transcript).